One of the fun things about having several books going at once is that it makes it easier for you see connections between them.

This morning I was reading Dorothy Sayers’ commentary on her translation of Purgatory. She describes the difference between the retributive punishment the characters undergo in Inferno as being very similar to the remedial punishments suffered by those on Mount Purgatory. The difference, she says, lies not in the nature of the suffering, but in the character of the sufferer. In Inferno, the people there have chosen their sin to the very end and so have no remorse – they do not accept the justice of their punishment, so the punishment can do them no good. On the contrary, those in Purgatory are there because they sincerely want to do the will of God and to be with him. They accept justice and “welcome the torment, as a sick man welcomes the pain of surgery” (p. 16). And they don’t just accept the suffering – they “count it all joy.”

Now, I’m a Protestant and don’t believe in Purgatory as a real state after death, but that doesn’t stop us from appreciating the story and from seeing what this means as an allegory of the soul. If we love and seek God, then the suffering we encounter in life is part of the refiner’s fire, and is for our good.

Then, this afternoon, I was rereading The Tempest to prepare for a co-op class I’ll begin teaching soon. In Act 2, a group of shipwrecked men are wandering around trying to find the rest of their companions. To one of these four men, Gonzalo, the island they find themselves on is a Paradise, or can easily be made one, but to the other three it’s “Uninhabitable and almost inaccessible,” with air that stinks of a swamp. The main difference between these men? Gonzalo is a faithful friend and counsellor, where his companions are all traitors and usurpers, “three men of sin,” as they’re called later in the play.

Not a perfect parallel, but it helped me make sense of what’s going on in that scene and another one that follows later, when the three men have a horrific vision, where Gonzalo sees and enjoys a banquet. The last time I read The Tempest I thought Gonzalo must be a lunatic.

Tuesday, February 23, 2021

The Divine Comedy and The Tempest

Saturday, February 13, 2021

The Faerie Queene

| |

| This is the Folio edition, illustrated by Walter Crane, which my family gave me for Christmas a few years ago |

Starting next August I’ll be teaching a year-long online class through House of Humane Letters. While all adults and high school aged students are welcome, I’ve designed the class especially with the homeschooling mom in mind, so we’ll be meeting in the evenings and following a schedule that’s looser than the traditional school year.

For each of the six books, I’ll have one introductory lesson, then we’ll read the book’s twelve cantos over the course of four weeks, then take a break before starting the cycle over again with the next book. All classes are recorded, so if you aren’t able to make the live class, you can watch the recordings and take things at your own pace.

Registration begins March 1 for families new to House of Humane Letters and will be conducted via email, so if you’re interested, go to House of Humane Letters and sign up for their email list.

Here’s my description of the class:

~*~ ~*~ ~*~

“From the time of its publication down to about 1914 [The Faerie Queene] was everyone’s poem—the book in which many and many a boy first discovered that he liked poetry; a book which spoke at once, like Homer or Shakespeare or Dickens, to every reader’s imagination.”

~ C.S. Lewis, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature

The Faerie Queene along with its style of storytelling has been out of favor for so long that we encounter several difficulties (apart from its sheer size!) when trying to read it. Lewis identified three for us: its narrative technique, its allegory, and the texture of its language—that is, the kind of poetry it is, which affects how it’s to be approached.

In this class, I’ll not only give you the imaginative frame of mind for entering into Spenser’s masterpiece, I’ll help you with these three areas. Together we’ll become more comfortable with the polyphonic narrative style, which you may never have encountered before. We’ll discuss how to understand the story’s allegory as well as when to ignore it. We’ll learn to appreciate Spenser’s poetic style and I’ll teach you strategies for reading the poetry, whether to yourself or to your children.

And that really is my goal for this class—not just to help you read this magnificent story, but to give you the confidence to read it to your own children as I did to mine.

Recommended editions (affiliate links):

I have found three editions which I can recommend for this class. Every edition has the same system of numbering the cantos and stanzas, so we can each use the one that best meets our own needs.

The single-volume Penguin Classics edition edited by Thomas Roche is the one I use when I’m reading aloud because there are no notes in the text, which I find distracting. All of the notes, which are in the back, are fairly minimal, defining unfamiliar words and giving some Biblical, Classical, and literary explanation of Spenser’s allusions. All spellings are original, which includes many instances of swapping V and U, using I instead of J, and swapping I and Y. Examples: Vna for Una, Sansioy for Sansjoy, Ioue for Jove, Yuory for Ivory. It’s a little confusing at first, but you do get used to it. Includes all the commendatory verses, dedicatory sonnets, and Spenser’s letter to Raleigh explaining his plan when writing the story. No essays or study guides.

The Routledge Press edition, edited by A.C. Hamilton. This is a large single-volume edition. Extensive footnotes defining archaic words and explaining Spenser’s allusions. Includes all commendatory verses, dedicatory sonnets, and the letter to Raleigh. Includes a chronology of Spenser’s life and work, a helpful introduction to the work, an extensive bibliography, and a list and description of all the characters and where they first appear in the work. Retains original spellings as described above. This edition is best for the student who wants to go deeper in his study of the work. A.C. Hamilton is a reliable Spenser scholar.

The Hackett Classics edition in five volumes (Books 3 and 4 are in one volume), various editors. Footnotes are minimal, defining difficult words and giving brief explanations of the allusions. When dealing with more “adult” allusions in the text, these notes tend to be more explicit than the notes in either Penguin or Hamilton. The introductions and essays vary in quality depending on the editor—some are pretty good, some are downright awful, so this edition is best for the reader who isn’t interested those extra essays. The commendatory verses and dedicatory sonnets are missing, but each volume contains the letter to Raleigh. Each volume has its own introduction (not always sympathetic to the work), bibliography, list of characters, and a glossary of the most commonly used difficult words. This edition has slightly updated spellings: uses of U, V, I, J, and Y are all regularized and some word use standard modern spellings to avoid confusion, e.g. “bee” updated to “be” because it’s the verb, not the insect. [Individual volumes: Book 1, Book 2, Books 3 & 4, Book 5, Book 6 and the Mutability Cantos]

Tuesday, February 2, 2021

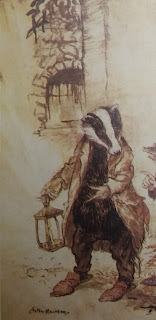

Badgers

“I’m a beast, I am, and a Badger, what’s more. We don’t change. We hold on.”

This is Trufflehunter in CS Lewis’s Prince Caspian, explaining to Nikabrik the dwarf why they must protect Caspian and restore him to his rightful throne: “Narnia was never right except when a son of Adam was King.”

Yesterday morning I was listening to Numbers chapter 4 and noticed how often badgers’ skins were mentioned. Over and over, as the tabernacle and its contents are described, it mentions a covering of badgers’ skins—seven times, in fact.

It’s not an accident that Trufflehunter and Mr Badger (from The Wind in the Willows) are the way they are. They endure. They protect the holy things.