This is the third post in a series.

Some of the editions I recommend below come with scholarly essays, but the important thing to keep in mind is what C.S. Lewis says about reading it in his chapter on Edmund Spenser in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature. He says that while reading commentaries can be helpful, they demand a certain kind of mindset that’s the opposite of the way we need to approach the poem itself.

Its primary appeal is to the most naïve and innocent tastes…. It demands of us a child’s love of marvels and dread of bogies, a boy’s thirst for adventures, a young man’s passion for physical beauty. If you have lost or cannot re-arouse these attitudes, all the commentaries, all your scholarship about “the Renaissance” or “Platonism” or Elizabeth’s Irish policy, will not avail. The poem is a great palace, but the door into it is so low that you must stoop to go in. No prig can be a Spenserian. It is of course much more than a fairy-tale, but unless we can enjoy it as a fairy-tale first of all, we shall not really care for it (132-3).

Audio

I haven’t mentioned this before, but another great way to experience The Faerie Queene is to let someone else read it to you. I highly recommend two versions:

Print

Free:

The Faerie Queene at Luminarium

This is the complete text in an easily navigable format. The drawbacks are that it has all the original spellings, and there are no notes on difficult words. Includes the letter to Raleigh and the commendatory verses and sonnets.

Low cost:

The single-volume Penguin Classics edition edited by Thomas Roche is the one I use when I’m reading aloud. It does not have the footnotes and marginal notes that I find distracting, but the margins are wide enough for me to add the notes that I do need.

- All spellings are original, which includes many instances of swapping V and U, using I instead of J, and swapping I and Y. Examples: Vna for Una, Sansioy for Sansjoy, Ioue for Jove, Yuory for Ivory.

- Includes all the commendatory verses, dedicatory sonnets, and Spenser’s letter to Raleigh explaining his plan when writing the story.

- No footnotes.

- Endnotes are fairly minimal, defining unfamiliar words and giving some Biblical, Classical, and literary explanation of Spenser’s allusions.

- Textual notes in an appendix. This is a section that tells all the variants in different manuscripts and how they’ve been reconciled in the text of the poem.

- Helpful glossary of common words.

- No essays or study guides.

Moderately priced:

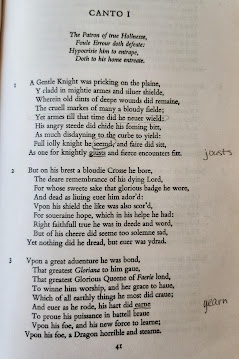

The Routledge Press edition, edited by A.C. Hamilton, who is a respected and reliable Spenser scholar. This large, single-volume edition includes a general introduction which is very helpful to the reader who’s just getting started in Spenser scholarship.

- Original spellings as described above.

- Includes all commendatory verses, dedicatory sonnets, and the letter to Raleigh.

- Extensive footnotes defining archaic words and explaining Spenser’s allusions.

- Textual notes in the back.

- Character list, including brief descriptions and where they first appear in the story.

- Extensive and valuable bibliography.

- Chronology of Spenser’s life and work.

The Hackett Classics edition in five volumes (Book 1, Book 2, Books 3 and 4, Book 5, Book 6 and the Mutability Cantos), various editors. Each volume has its own introduction, which is not always sympathetic to the work, depending on the editor—some are pretty good, some are downright awful, so this edition is best for the reader who isn’t especially interested in those extra essays.

- Slightly updated spellings: uses of U, V, I, J, and Y are all regularized and some words use standard modern spellings to avoid confusion, e.g. “bee” updated to “be” because it’s the verb, not the insect.

- Includes letter to Raleigh, but commendatory verses and dedicatory sonnets are missing.

- Footnotes are minimal and generally helpful, defining difficult words and giving brief explanations of the allusions. When dealing with more “adult” allusions in the text, these notes tend to be more explicit than the notes in either Penguin or Hamilton.

- Textual notes in the back.

- Glossary of most commonly used difficult words.

- Index of characters.

- Bibliography.

Expensive, and out of print, but glorious if you can afford them:

The Folio edition, with illustrations by Walter Crane.

- Walter Crane’s enchanting illustrations and the excellent physical quality of the book are the main reasons for owning this one.

- Very slightly updated spellings (they’ve modernized the usage of I/J and U/V), but otherwise original.

- No notes or essays.

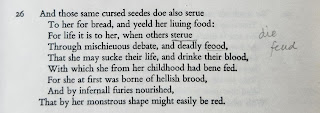

The Variorum

Complete Works of Edmund Spenser, in eleven volumes, ed. Erwin Greenlaw, Charles Grosvenor Osgood, and Frederick Morgan Padelford, 1932. The first six volumes contain all the books of

The Faerie Queene. The remaining five are all of Spenser’s prose and poetic works, a

Life of Edmund Spenser by Alexander Judson, and an index to the poetry.

- The main attraction of this one is all the scholarly commentary. I mean ALL the scholarly commentary. It contains everything in every language (untranslated) that was available when it was published.

- Original spellings.

- Includes all commendatory verses, dedicatory sonnets, and the letter to Raleigh.

- No footnotes.

- Extensive endnotes explaining literary allusions, historical background, the allegory, the roles of certain major characters, and more. Each volume has one book of the Faerie Queene that takes up about a third of the volume. The other two-thirds is commentary.

- Ideal for the uber-nerd like me who wants all the commentaries!

- Have I mentioned all the commentaries?

Of interest:

Oxford edition, published 1909, edited by J. C. Smith. This is meant to be an authoritative text, so it contains all original spellings. The introduction gives some historical background on the publication and revisions of the poem and explains the editor’s philosophy and method. The footnotes are all differences in the texts of the various manuscripts. Contains the letter to Raleigh, commendatory verses and dedicatory sonnets, and has an appendix with longer critical notes.

And now, unfortunately, I have two anti-recommendations.

The first one is the one published by Canon Press. So far they only have the first three books out, and I’ve only read the first one, Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves, edited by Roy Maynard. This is the updated and annotated edition that I bought when I first wanted to read the Real Deal. The updated spellings are the only thing this edition has going for it. Where Maynard updates the language he sometimes errs, and he frequently gives bad definitions in the margins, so it seems that he doesn’t actually understand the language of Spenser. Worse, his explanatory notes are heavily agenda-driven—he makes it seem like Spenser was an anti-Catholic Puritan. Lewis says that this was not the case. In Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, Lewis says that although Spenser was educated at Cambridge, he never became attached to the two intellectual movements of the day, Puritanism and what we now call the Neo-Classical movement, the “young, fierce, progressive intellectuals, very fashionable and up-to-date,” who were united by their “hatred for everything medieval: for scholastic philosophy, medieval Latin, romance, fairies, and chivalry.” This one probably won’t kill your love of Spenser if you read, but I can’t recommend it since there are so many better options.

This edition is missing the letter to Raleigh and the commendatory verses and sonnets.

~*~ ~*~ ~*~

The second one hasn’t been published yet, but it’s received a lot of publicity in my circles. This is the “modern prose rendering” by Rebecca Reynolds. I have read one of the cantos, which Reynolds forwarded me so my son and I could read it. I’m not at liberty to share anything about the text, but I will note that if you’ve read Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf, you’ll have an idea what to expect from this edition. Tolkien first made that translation early in his career as an Old English scholar and revised it continuously for the rest of his life. It was his personal study of the language of the poem, and should be seen as an exercise in linguistics, not as a work of art. That is, Tolkien’s Beowulf is not a literary translation meant to delight the reader. Rather, it’s a textual and linguistic study of the poem, which is why so many people were disappointed when they finally received their much-anticipated copy of it.

Where Maynard in his Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves seems not to understand the language of Spenser, Reynolds seems not to understand the form of Romance itself, including its use of stock characters and its way of using metaphor to point to transcendent reality. In her “Introduction to Books Five and Six,” while explaining that all of Spenser’s knights fail in their quests to one degree or another, Reynolds says that

the title knights of Book Four would have killed one another, had not their lethal conflict been resolved through a magic potion inaccessible to the average reader. (Spenser has claimed that the Faerie Queene instructs readers how to live virtuously. Where does he expect them to find such a potion?)

This, in a teacher of literature, is inexcusable ignorance of the way magic works in a Romance. A Romance is essentially a long, literary fairy tale, and fairy-tale magic of this sort works in the fairy-tale world the way the grace of God works in our world—you don’t find it; it finds you. She consistently discusses Spenser’s treatment of characters as if they were people living in our world, and not characters in a secondary world, an imaginative world of Spenser’s creation, and specifically characters in a story with a long literary tradition behind it. In the “Introduction to Book One,” she says, “Spenser’s treatment of women sometimes employs the extremes of angelic young ladies and wicked old enchantresses, females typed instead of embodied.” But this is exactly the way the medieval Romance works. It’s not a modern realistic novel.

Reynolds repeatedly makes the biographical fallacy of thinking that understanding the author helps you understand the story. In her “Introduction to Book One,” she writes pages of commentary explaining “Spenser’s questionable treatment of race, religion, gender, and nationality,” saying he glorifies whiteness and objectifies women, and writes extensively on “Spenser’s Anti-Irish Behavior,” among other atrocities. This is the topic of “Elizabeth’s Irish policy” that I mentioned when quoting Lewis at the top of the blog post. In

Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, Lewis says, “The many generations who have read and re-read

The Faerie Queene with delight paid very little attention to the historical allegory; the modern student, at his first reading, will be well advised to pay it none at all.” Reynolds is taking exactly the opposite approach, pointing out all of Spenser’s supposed flaws, according to very modern (may I even say “woke”?) standards.

Which brings me to the last area of concern that I’ll be addressing here. The major issue with this edition is the same as with Maynard’s: it’s highly agenda-driven. I have read all the introductions that are available on the website, and I encourage you to do a web search and download and read the essays for yourself for more information. The introductions are quite long, so I will include here a longer selection from the “Introduction to Book One” to illustrate this agenda.

Spenser made some grave mistakes as a writer and as an Englishman living in Ireland. Perhaps it could be helpful for you to read about some of his shortcomings and how I handled them before beginning this book. Where I didn’t sterilize Spenser, it was out of a conviction that we need an accurate record of the past to help us make our present and future better; I don’t think we can overcome wrongs by denying they existed. Where I muted him a bit, it was out of a desire to instill respect where there was once hostility….

As a reader, I’ve given myself permission to shout disagreements with Spenser here and there.... I welcome you to both rage at him with me and glean alongside me as we read his tale. May our journey through this and all old stories be indignant and supple at all the right moments.

...

Throughout the text, I couldn’t resist including a few maternal footnotes for young female readers who may be encountering the jolt of objectification in a historic work of literature for the first time. Though I couldn’t address every instance of sexism, I want these intermittent messages to serve as a little hand squeeze for the youth wandering through these stories. Ladies, if you feel angry over how a female is treated in a given scene, I’m likely right there with you. Let’s stare unflinchingly into the hard realities that our foremothers have faced. Let’s learn from the past.

In summary, Reynolds claims to love

The Faerie Queene. She says she hopes that “this rendering will help both younger students and curious adults with busy lives who simply don’t have the time or training to untangle four-hundred-year-old language.” She says that she hopes people will read her prose rendering and then go on to read an edition such as Hamilton’s. But it seems to me that Reynolds’ approach will have the opposite of the intended effect.

~*~ ~*~ ~*~

To read other things I’ve written about The Faerie Queene over the years, please click the Faerie Queene tag. Happy reading!