I don't think I've mentioned this here before, but since I'm technically a retired homeschool mom now, I've been taking a French class at the local college. It's something I've wanted to do for decades, so I'm grateful for the opportunity to do it now. Let me tell you, it's not easy learning a new language at my age, but it has been fun. For the final exam, the professor wanted each of us to do a "surprise" project, so I wrote a fairly brief version of the Cupid and Psyche story, which y'all know I love, and told it for the class -- partly from memory, but thankfully she let us look at our notes because actually DOING it made me forget nearly the whole thing. Anyway, for your amusement, here's the story, along with my introductory remarks.

~*~ ~*~ ~*~

Je vais vous raconter l'histoire de ce tableau. Il s'appele "The Wedding of Psyche," ou "Le Mariage de Psyché" par le paintre Edward Bourne-Jones.

|

« L’Histoire de Cupidon et Psyché »

Il était une fois un roi qui avait trois filles. La cadette était si belle que Vénus est devenue jalouse d’elle. Elle a envoyé son fils faire tomber Psyché amoureuse d’une bête, mais quand il l’a vu, il est tombé d’amoureux, et il a désobéi sa mère.

Il a demandé aux autres dieux de l’aider, alors l’oracle d’Apollon est allé vers le roi, et il l’a dit, « Donnez votre fille en mariage à la bête à la montagne. »

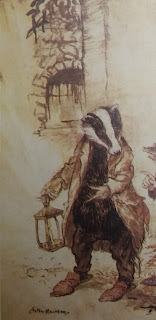

Ici, nous voyons Psyché et ses demoiselles aller à la montagne.

Elle est montée seule, et elle a attendu. Bientôt, Zephyrus est arrivé et il l’a apporté vers un grand château. Les portes se sont ouvertes et une voix a dit, « Bienvenue à chez vous, Madame. »

Psyché est entrée dans le château, et elle a vu toute chose elle avait besoin.

Quand la nuit tomba, son mari est venu. Elle n’a pu pas le voir parce qu’il faisait noir, mais sa voix était gentille.

Il lui dit : « Je t’aime et j’espère que tu seras heureuse ici. Tu peux avoir tout ce que tu veux. Mais il y a une chose que tu ne peux pas faire – ne me vois pas dans la lumière. »

Le temps a passé, et Psyché était heureuse.

Un jour, ses sœurs sont montées, et Psyché est sortie pour les rencontrer. Quand ses sœurs l’ont vu, elles sont devenues jalouses.

Elles ont dit, « Pourquoi es-tu si heureuse quand tu es mariée avec une bête ? »

« Non, » a dit Psyché, « il n’est pas une bête ! »

« Alors, » ont dit ses sœurs, « tu dois découvrir la vérité. » Et elles lui ont dit quoi faire.

Quand elle est rentrée chez elle, Psyché a tenu une lampe allumée, l’a recouverte, et l’a cachée dans sa chambre. Après que son mari a dormi, Psyché a pris la lampe, et l’a découverte.

Et ce qu’elle a vu ! En vérité, son mari n’est pas une bête ! Il est le Dieu d’Amour !

Immédiatement, Cupidon s’est réveillé et s’est crié, « Qu’as-tu fais ? »

Il s’est envolé et Psyché est devenue triste. Elle l'a cherché, et elle ne l'a point trouvé.

Enfin, elle est allée vers Vénus, et elle a dit, « Je suis désolée. S’il vous plaît, donnez-moi mon mari, celui que mon cœur aime ! »

Vénus a dit, « Jamais ! » et elle lui a donné des tâches impossibles.

Enfin, elle a dit, « Va chercher la potion de beauté de Perséphone, et donne-la-moi. »

Psyché est descendue à Hadès, et après beaucoup de souffrance, elle est retournée à la terre, avec un vase d’albâtre. Elle a voulu un peu de potion pour se rendre belle à nouveau pour son mari.

Mais la potion de beauté de Perséphone est le sommeil, et quand elle a ouvert le vase, elle est tombée par terre comme si elle était morte.

Pendent que Psyché travaillait et souffrait, Cupidon était sous les verrous, parce que sa mère était furieuse. Mais quand Psyché est tombée, il a brisé les verrous, et s’est envolé vers elle. Il a pris le sommeil de ses yeux, et l’a porté au ciel, où il a demandé de l’aide à Jupiter.

Ensuite, Jupiter a réprimandé Vénus, et Psyché a été faite une déesse, et tous les dieux l’ont reçue comme la femme de Cupidon.

Bientôt, leur enfant est née. Elle s’appelle Plaisir.

Fin.